/Aug

2022

Ana Paula, head of technical development tells us about working at Viúva Lamego since the 1990.

You joined Viúva Lamego in 1990. How was manufacturing and product development back then?

When I joined, after graduating in Chemical Engineering at the Instituto Superior Técnico, the factory was still very much in the nineteenth century. We were in the middle of Lisbon and we were still working with wood kilns, for instance. The neighbours complained that their clothes smelled of firewood, we had buildings being built on our doorstep. The city had grown and reached us, just as had happened with the first Viúva Lamego factory that this one had replaced, the beautiful blue-and-white-tiled façade in Largo do Intendente.

Initially, my job was to help with the change of facilities and to bring in a more organised approach to the way we worked: the manufacturing process, quality control, etc. Up until the nineties, the legacy of secrecy still had a huge impact on the way we worked. There wasn’t much of a culture of sharing technical or artistic knowledge in Portugal. To give you an idea, Manuel Cargaleiro, who still has his workshop with us here, once told me that when fellow artist Jorge Barradas found out he was to start teaching, he kicked him out of the atelier they shared, fearing that Cargaleiro would divulge his methods and techniques to his students.

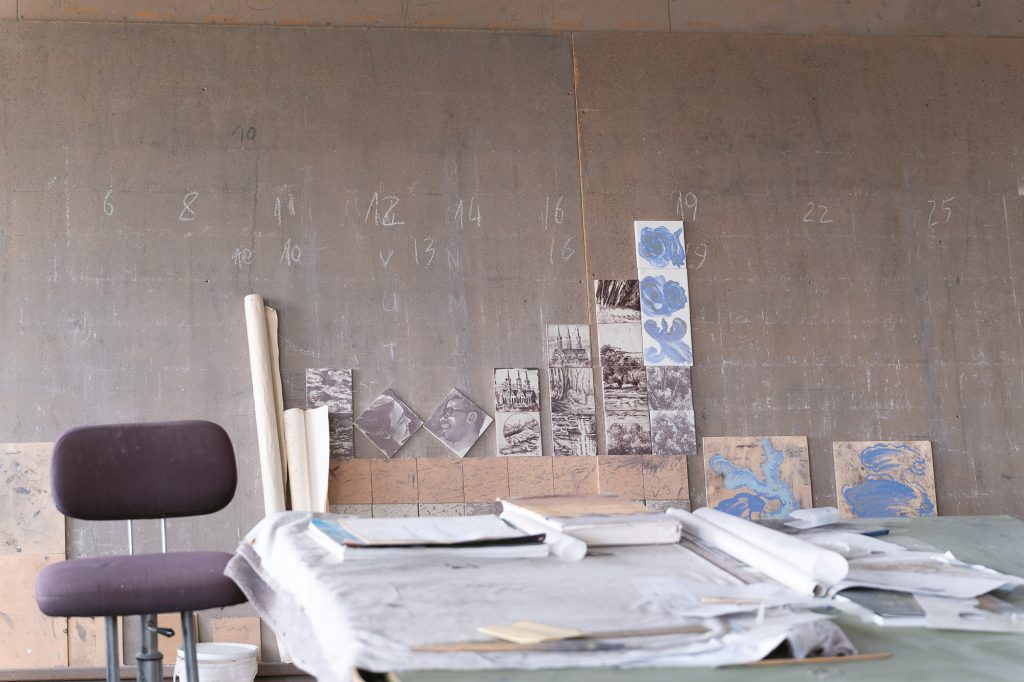

For us, this legacy of secrecy meant things such as having trouble reproducing an exact colour, because nothing was registered, we didn’t have a technical approach to creating colours. Today we have a structure and a team that’s technically much more evolved. And artistically, we now benefit from the existence of better schools, on which we can rely when looking for trained and talented painters, for example. All our painting is manual, so painting remains a crucial aspect for us.